This post revolves around changing my mind about The Brutalist after a good conversation with friends and seeing No Other Land. I always think of essays as a place where people can and should change their minds, but reviews can be a trickier venue where convictions are needed to take a certain position on a piece of art. This is my attempt to change my mind after and from within my original perspective.

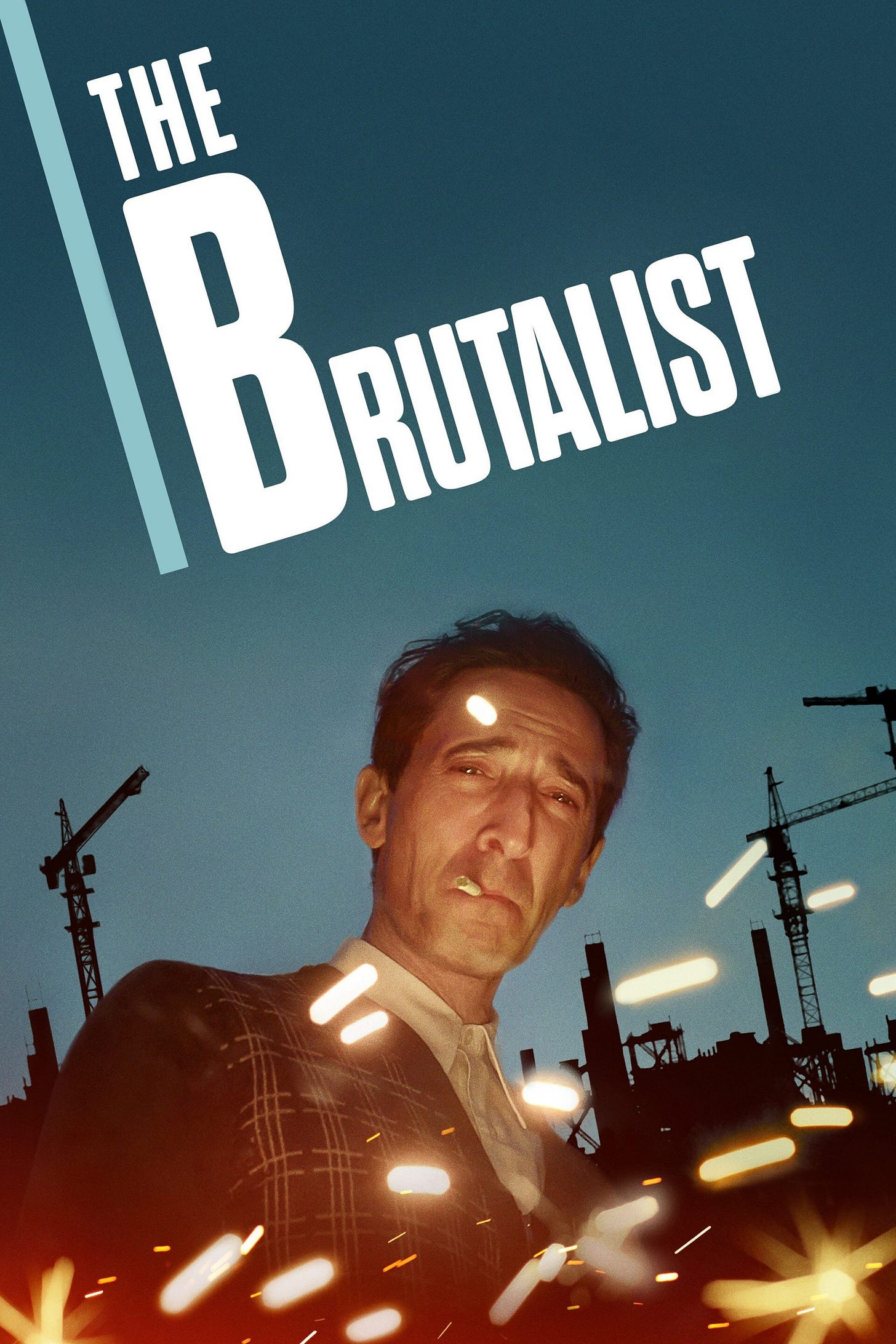

The Brutalist

dir. Brady Corbet

An immigration story that undoes the American myth, The Brutalist is a monument unto itself, an incredible undertaking about an architect who must rebuild his life in a country that promises newcomers dreams but only delivers them at great costs.

László Tóth (Adrien Brody) arrives in the States in the wake of the Holocaust, sacrificing his life as a famous architect for a semblance of safety. He longs to reunite with his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), who writes to him in earnest, but he settles into a life of labor and anonymity, suffering abuses as his world is turned on its head, much like the Statue of Liberty in the opening scene.

After being plucked from obscurity by a wealthy man (Guy Pearce), Tóth’s life turns upside down again, tasked with building a monument to American wealth and Christianity, despite his Jewish identity.

The film’s runtime is perhaps what many who haven’t seen it know it for: three hours and thirty-four minutes, a fifteen-minute intermission included. It’s best to be surprised along the way by what happens, lest you find yourself clocking the time. I even wished the bookshelves shown in the trailer had been hidden from me until I saw it, their reveal in the film so awe-inspiring. But The Brutalist more than earns its runtime, with an intricate script by Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold, an incredible score by Daniel Blumberg, and actors at the absolute top of their game.

By the time it all comes apart, the story is a damning unraveling of America and Chirstendom, a pointed finger at the abuse of power, wealth, and the vulnerable. Inspired by his own family’s immigration struggles, Brody gives a powerhouse performance that helps in making The Brutalist an American masterpiece, in spite of the country’s empty promise of a dream very few can access without paying tremendously.

After my initial review of The Brutalist, where I walked away impressed and not a little taken aback by its grandeur, a friend sent me this Screen Slate article by Noah Kulwin. I admit I was initially against Kulwin’s logic, the ambiguities of the film he reads in a certain light, essentially suggesting that Zionism is perhaps at the root of The Brutalist’s arc, whether or not it’s willing to say so definitively. I wasn’t keen to pin a certainty in the ambiguities, whereas Kulwin finds this to be evasion rather than mystery.

I was perhaps defensive, hoping not to be so easily fooled into loving a movie so much I could miss an entire thread that quietly builds up Israel as a monument that is not so corrupt as the United States is made out to be. How could I see The Brutalist as a movie that undoes an empire while other friends saw another empire bubbling underneath?

While discussing the article, a friend brought Kulwin’s review home to me, illuminating how the character of Zsófia, Tóth’s niece, only finds the voice she lost as a child when she speaks of Israel as home. I had seen László and Erzsébet’s own defensiveness to this declaration as a negation of her idea, but the film’s epilogue—which I confess I did not entirely grasp after being struck by the initial “ending”—arguably doubles down on this equating of voice and home with the Israeli state. And, as Kulwin writes, the making of Israel as a home came at the cost of brutalizing others—namely, Palestinians.

I thought The Brutalist was one of the best movies of 2024. At one point, I was totally fine with it being considered the best picture of the year, even if it wasn’t my personal favorite. I still think it’s a successful film, and I will rewatch it at home at some point and still appreciate many aspects of its construction. But I am now more skeptical of its underpinnings, the cracks in its foundation that have been revealed to me. If we are going to tear down empires, we can’t do so with the intent of building up others.

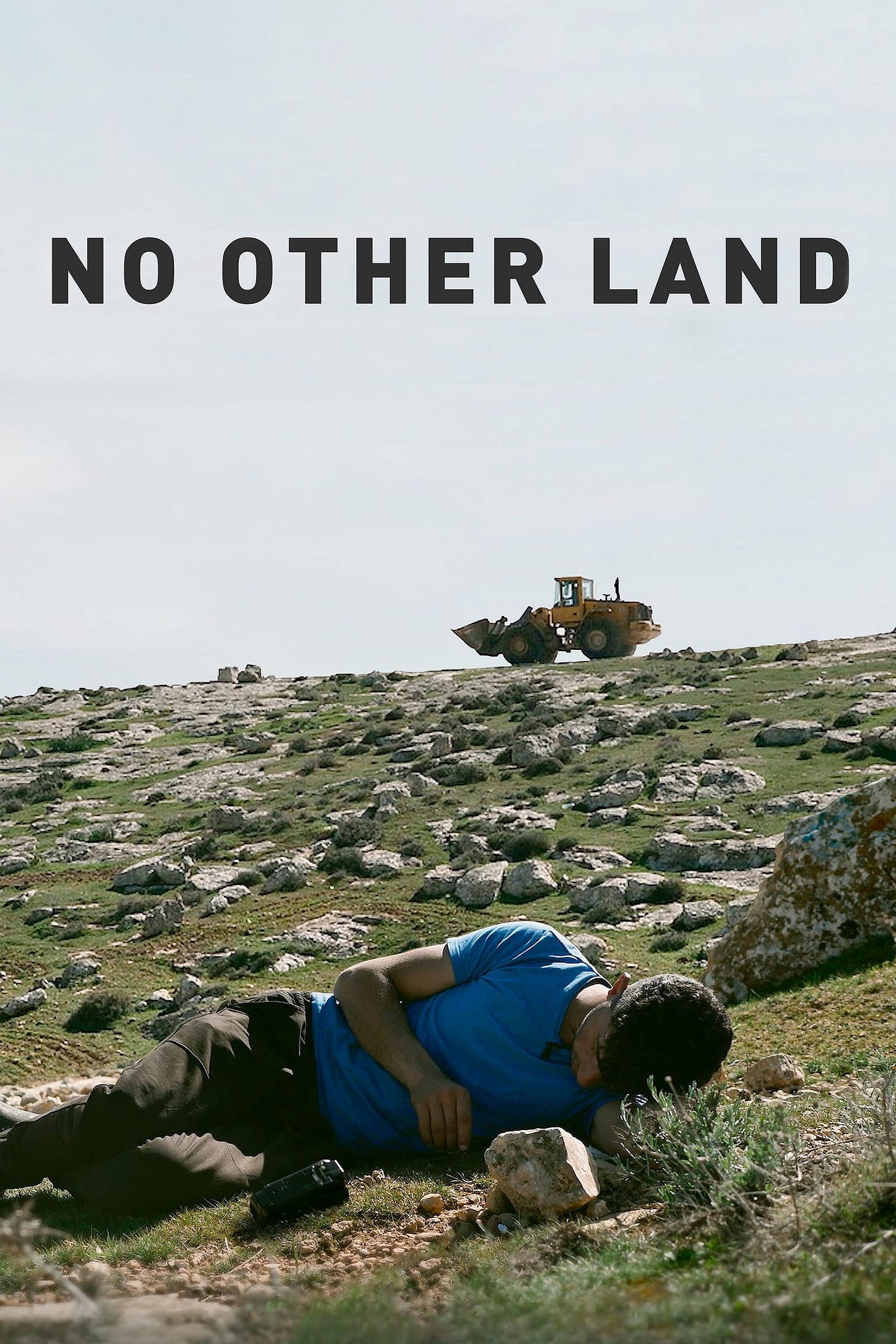

No Other Land

dir. Rachel Szor, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham, Basel Adra

This weekend I saw No Other Land at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre. The film is nominated for Best Documentary at the Academy Awards. Filmed by a collective of journalists, it follows the villages of Masafer Yatta, in the occupied West Bank of Palestine. For years, the Israeli army has been destroying the villages, claiming the land as their own for the purpose of becoming “military training grounds.”

The villagers have fought back by protesting, filming, and attempting to rebuild their homes amidst the Israeli-created rubble. They fought to go to court over the land, and when granted a trial in an Israeli court, the court ruled that the Palestinians have no right to the land. In an Orwellian turn, they are told to “take it up with the law,” a law that doesn’t acknowledge them as having rights at all. License plates for the Israeli people grant them the ability to drive anywhere, while license plates for the Palestinian people bar them from driving most places.

It’s confounding to see so much unused land, inhabited by farmers in small homes scattered throughout, while the IDF systematically destroys what little seems to be there, apparently only for the sake of asserting dominance over others. Children are kicked out of their school and forced to watch it bulldozed. Chicken houses are knocked over before all of the chickens have fled. Playgrounds are torn down. Brutality proliferates. Power wields itself eternally.

Basel Adra has been documenting the takeover of Masafer Yatta for years, following his dad’s activism and risking his life to film and report on what he has seen, in the hopes of enough people seeing it that something changes. Yuval Abraham, an Israeli journalist, joins him in his efforts to document, to bear witness to the destruction propagated by his people. Their conversations reveal the exhaustion of activism, the privilege Yuval must reckon with, the cost of fighting versus giving in, the kind of hope it takes to sustain after decades of oppression.

No Other Land is disturbing, a damning picture that leaves no room for equivocating. Israeli soldiers shoot a man—Harun Abu Aram—on camera, as he holds on to the generator that powers his home as soldiers try to take it from him.

In one scene near the end, the villager’s water source is destroyed, cited as illegal by the IDF while a Palestinian man insists it is a human right. That someone would have to insist this truth is just one of many details that left my theater quiet as the credits rolled and we sat, unable or unwilling to look away from what the filmmakers demanded we see: their existence, their humanity, their continued fight for dignity and a place to call home.

“My entire existence became about having a home,” a man says. It’s a sentiment that the fictional Tóths might understand, but the perceived distance between brutalities can be so hard to bridge. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t work to do so.